Ancient authors described Baia as an enchanting place not far from Rome, blessed by Nature and a mild climate, and at the same time as a place of damnation, where drunk young people enjoyed themselves on the beaches until the break of dawn, while prudish, Penelope-like women were quickly becoming dissolute and scantily clad like Helen of Troy. For centuries, Baiae was the place associated par excellence with otium. Its luxury villas were firstly built around the Lacus Baianus since the beginning of the I century B.C., and then, starting from the following century, were squeezed among the lavish palaces of the emperors who chose Baia as their residence. A natural landscape of rare beauty, made of yellow tuff rocks and a lush vegetation, was transformed in a crowded seaside town where everyone could enjoy the pleasures of life.

Numerous natural hot springs – a gift from the same volcanoes that centuries later would have condemned Baia to a collapse by bradyseism – attracted important personalities from the late republican and imperial Rome.

These boiling water veins were captured and wisely regimented to become swimming pools and bathhouses, or thermo-regulated vats for fish and oyster farming.

Baiae was easily accessible from the Romans who spent their lives between the Forum and the other centres of power, both from Roman roads and the nearby port of Puteoli, the chaotic hub of a gigantic network of shipping routes.

Julius Caesar, the Emperor Claudius, the members of the Severan dynasty, as well as Seneca and the gens of Calpurnii Pisones had their residences there; some of these are now located below the modern village of Baia, in the municipality of Bacoli.

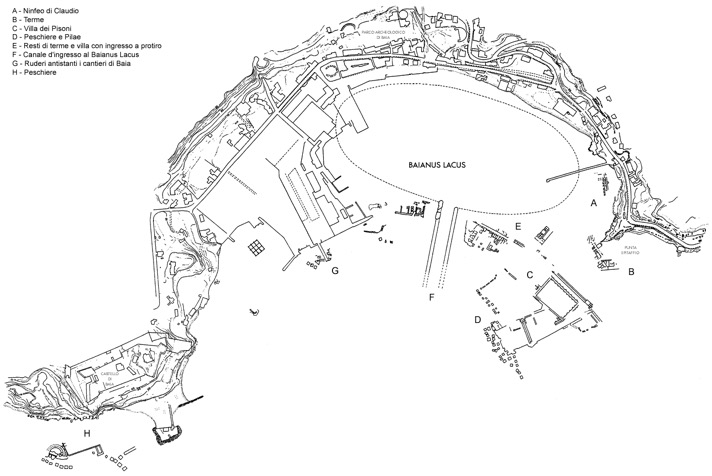

The other villas are now submerged at a depth of 0-6 meters and located on the seabed between the fragile tuffaceous ridge of Punta dell’Epitaffio and the hilltop on which the Aragonese Castle was built many centuries later. Today the Castle is home to the National Archeological Museum of Campi Flegrei.

The underwater remains are protected thanks to the institution of the PArcheological Underwater Park of Baiae and may be visited by everybody for a scuba diving experience, snorkelling or rides on a boat with a transparent bottom, or by means of 3D virtual reality.

The protection of this underwater treasure, unique in the whole world and continuously exposed to natural, physical, biological and man-made degradation, is one of the greatest challenges in underwater archaeology.

ISCR, in collaboration with other heritage protection agencies, has been active for some time in the conservation of the submerged structures in Baiae with the project Restaurare Sott’Acqua (Restore Underwater) and the new projects MUSAS, IMARECULTURE, BLUEMED, SYBILLA, and ARTEK.

The Archeological Museum

The Archaeological Museum of Campi Flegrei, opened in 1993, collects the objects coming from Baiae, Puteoli, Cumae, Misenum and Liternum inside the evocative rooms of the Aragonese Castle of Baia, a fortress whose construction begun in 1495 on a hilltop overlooking the sea. The terraces were home to a maritime villa, traditionally attributed to Caesar.

Apart from a rich collection of statues, inscriptions and artefacts coming from the archaeological excavations carried out in the Phlegraean Fields, the Museum has a vast collection of materials of underwater origin on display. These were recovered throughout the years after researches and surveys conducted in the waters of the ancient Gulf of Baiae, the quay of Ripa Puteolana and the area of Misenum.

Among the most interesting sections, there are the reconstructions of the Nymphaeum of Punta dell’Epitaffio and the Sacellum of the Augustales of Misenum, inside the tower called Tenaglia.

Another element of particular interest are the twenty rooms dedicated to the Roman port of Puteoli, a great example of late-Republican and Imperial cosmopolitanism and trades. The rooms contain inscriptions and sculptures that confirm the presence of foreigners and an evocative reconstruction of the Cave of Wadi Minayh in the Egyptian desert, where epigraphic testimonies of the presence of resourceful mercatores from Puteoli had been found.

Miniero, P. (2003) Baia. Il Castello, il museo, l’area archeologica. Napoli.

Zevi, F. and Miniero, P. (2008) Museo Archeologico dei Campi Flegrei, Catalogo generale, 3, Baia, Liternum, Miseno. Napoli

Insights

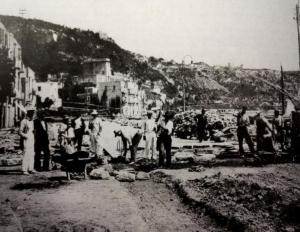

Between 1923 and 1928, with a hiatus in 1926, the harbour of Baia underwent heavy dredging works to enlarge the port quay and level the seabed. During these years, many works of art were discovered with a notable number of carved architectural elements. The majority of them were attributable to one section of the ancient imperial palace on the Lacus Baianus.

The discovery of numerous lead pipes (fistulae aquariae), some of them bearing the stamps “L. Septimi Severi Pert. Aug.” and “Septimi Severi”, allowed for attributing one of the buildings affected by the dredging works to the Severan age. Probably it was a nymphaeum, built in the Flavian age as confirmed by other fistulae with the name of the emperor Domitian, and then restored in an consistent manner with new marble decorations under Septimius Severus (193-211), Carcalla (198-217) and Severus Alexander (222-235).

Works at the port quay of Baia during the 1920s (photo: Archivio Alinari)

During the 1990s, the archaeologist Fabio Maniscalco retrieved the documents from the archive and reorganized the material recovered during the 20s and conserved for a long time in the depots of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. He proposed a reconstruction of the building according to the model of similar structures, like the Septizodium and the Nymphaeum of Severus Alexander in Rome, hypothesizing a reconstruction of the entire Domitian water infrastructure under Septimius Severus, a rebuild of indoor and outdoor spaces (water outlets and vats) under Caracalla, and the last servicing done under Severus Alexander. A fire would have eventually marked the last days of the building, as there are numerous burns on the recovered marbles.

REFERENCES

Maniscalco, F. 1995, ‘Un ninfeo severiano nelle acque del porto di Baia’, Ostraka, 4(2), pp. 257-271.

Maniscalco, F. 1997, Ninfei ed edifici marittimi severiani del Palatium imperiale di Baia. Napoli: Massa Editore.

Zevi F. (cur.) 2009, Museo archeologico dei Campi Flegrei. Castello di Baia. Napoli: Electa Napoli, vol. 3.

The passion developed by the wealthiest classes of the late-republican Rome for the works of art made in the Greek world, after an initial rush for the originals by collectors, gave birth to a thriving market of copies. Many of the most representative statues of the ancient Greece, particularly for the classic and Hellenistic models of Phidias, Polykleitos, Praxiteles, Skopas and others, are known to us not only thanks to numerous mentions and descriptions in literature, but especially thanks to a great number of replicas created during the Roman age for more or less sophisticated and cultured buyers.

Due to an outstanding concentration of seaside villas and luxury residences around the Lacus Baianus and the entire coast of Campi Flegrei, it is not surprising that Baia was home to numerous copyist workshops, as they were capable of replicating ad infinitum the most famous masterpieces of Greek art. Therefore, among various underwater discoveries, several statues were already well known at the times by Roman antiquarians, while others were the typical out-of-context replicas, transformed in fountain spouts or banal decorations for private gardens.

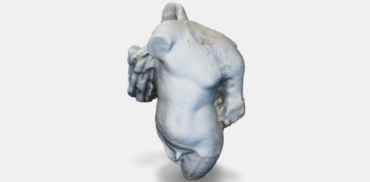

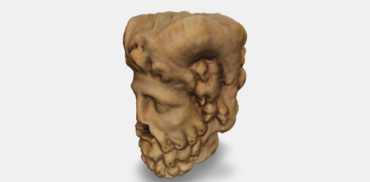

Among the most interesting copies kept at the Archaeological Museum of Campi Flegrei, we can list a fine Amazon’s Head, a Statue of the type known as Hera Borghese, a Statue of Tyche, (perhaps a part of an Artemis), a bearded herm, a lying Heracles, a torso of Eros, a statue of Athena of the type known as Vescovali-Arezzo, a fine sculpture Group of Psyche and Cupid.

REFERENCES

Zevi, F. (2009) Museo archeologico dei Campi Flegrei. Castello di Baia. Napoli: Electa Napoli.

The underwater Park

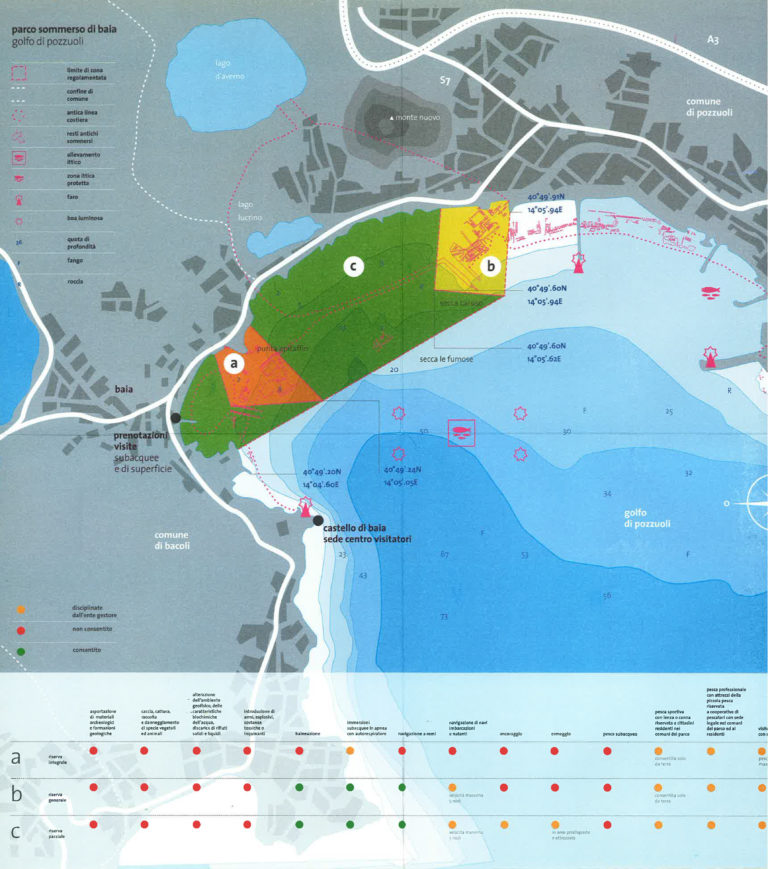

Established on 7th August 2002, the Underwater Park of Baiae covers an area of 177,7 hectares delimited by western boundaries of the ancient Lacus Baianus, below the Aragonese Castle of Baia (home to the National Archaeological Museum of Campi Flegrei) and the former industrial estate on the coast of Pozzuoli, at the heart of the ancient waterfront of the trading port of Puteoli.

The creation of the Protected Marine Area and of the Underwater Park is the culmination of a legal and cultural battle fought for years by institutions and citizens to protect this unique archaeological heritage, incredibly and continuously exposed to threats caused by the numerous manufacturing sites and businesses rooted in the area.

The villa of the Pisones, the villa with prothyrum entrance, the Nymphaeum of Punta Epitaffio, the via Herculanea, Portus Julius, the pilae of Secca Fumosa and other archaeological sites included in the Park are protected according to a zoning system that provides for different levels of protection: zone A: the Nymphaeum of Punta Epitaffio, Villa of the Pisones, villa with prothyrum entrance and the remains of the imperial Palatium; zone B – Portus Julius; zone C – Secca Fumosa and the areas between the zones A and B.

Activities such as scuba diving, snorkelling, canoeing, visits on a boat with a transparent bottom and sailing are strictly regulated.

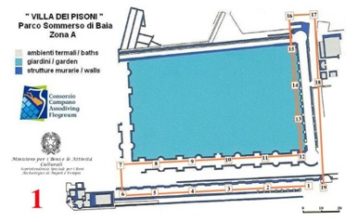

Villa of the Pisones

A magnificent residence built between the Lacus Baianus and the long port basin of Puteoli, the so-called Villa of the Pisones constitutes one of the most striking examples of the Romans’ ability to build along coasts and promontories, or even directly in water, with an exceptional architectural effort.

The villa, in fact, is one of many villae maritimae built by the late-republican elite, particularly along the Tyrrhenian coasts of Italy since the end of the II century B.C. In the early construction stages, it took advantage of the outer section of the calc-tufa promontory of Punta dell’Epitaffio, now considerably shrunk back due to erosion and bradyseism. This first nucleus, whose boundaries are still not very clear, occupied one of the most pleasant places on the Phlegrean coast, taking advantage of a nearly 270-degree view on the Gulf and an exceptional exposure to the South.

What is obvious is that the owners enhanced the villa one generation after another, embellishing it with luxury quarters, terraces with a sea view, at least one fishery for fish farming and preserving, and three long piers.

A fortunate discovery of a lead pipe with a stamp allows for clarifying that, at least during the early Imperial age, the whole complex belonged to the rich and influential family of Calpurnii Pisones (it is worth remembering that the gigantic Villa of the Papyri, discovered in the immediate vicinity of Herculaneum, was attributed to one of its members).

Therefore, it was confirmed that the villa was the famous Villa of the Pisones, confiscated and transferred to the imperial possessions following an unsuccessful conspiracy against the emperor Nero.

Once it became part of the direct possessions of the Emperor, the villa was expanded again, as it could finally occupy

also the strip of land that separated it from the Palatium of Punta Epitaffio and its large Nynphaeum-Triclinium.

The large site can be visited today at a depth of 4/6 meters, at a short distance from the modern port of Baia. It features structures and mosaics related to several phases, and in particular to the period in which the emperor Hadrian – who had a unique relationship with Baiae – ordered new expansions, among which the colossal viridarium, a garden surrounded by porticoes with a number of large windows, niches and half-columns that are clearly related to the Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli.

Among the noteworthy structures belonging to the Villa, apart from the already mentioned viridarium that stands as the main visiting route for many divers who explore this part of the Underwater Archaeological Park of Baiae, there are numerous mosaics (some of which were restored by the NIAS of ICR, and private baths, a very common feature of the maritime villas in the Phlegraean area that, thanks to the presence of volcanic thermal springs, quickly occupied the whole coastline.

The research carried out during MUSAS project – aimed at creating a three-dimensional reconstruction of the villa and at getting a better understanding of the most ancient phases of the complex – allowed for assuming the presence of a lighthouse located on the furthermost point of the promontory, resting on a great pylon of concrete that was directly attached to the villa through a small pier. The most interesting result though, reconstructed on the basis of the topographic survey of the seabed and maritime works, was the discovery of an extraordinary terrace built on stacks of pilae, resting directly on the seabed, at the southern end of the villa. This the first clear archaeological evidence of what was stated in the sources: once the space ran out in Baiae, the wealthy owners willing to build other villas went so far as to build in the sea.

Borriello, M. and D’Ambrosio, A. (1979) Baiae-Misenum (Forma Italiae. Regio I, XIV). Firenze.

D’Arms, J. (1970) Romans on the Bay of Naples: a social and cultural study of the villas and their owners from 150 B.C. to A.D. 400. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Davidde, B. et al. (2014) ‘Mosaic marble tesserae from the underwater archaeological site of Baia (Naples, Italy): determination of the provenance’, European Journal of Mineralogy.

Davidde, B., D’Agostino, M. and Stefanile, M. (2019) ‘Tra conoscenza, valorizzazione e nuove tecnologie: il progetto MUSAS’, Forma Urbis, 2.

Davidde, B. and Gomez de Ayala, G. (2016) ‘Laser scanner reliefs of selected archaeological structures in the submerged Baiae (Naples)’, in The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W5, 2015 Underwater 3D Recording and Modeling, 16–17 April 2015, Piano di Sorrento, Italy.

Davidde, B., Petriaggi, R. and Gomez de Ayala, G. (2013) ‘3D Documentation for the Assessment of Underwater Archaeological Remains’, in Archaeology in the Digital Era, vol. II, e-Papers from the 40 th Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology Southampton, 26-30 March 2012. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 174–180.

De Franciscis, A. (1970) ‘Baia’, Enciclopedia dell’Arte Antica, suppl.

Di Fraia, G. (1993) ‘Baia sommersa: nuove evidenze topografiche e monumentali’, in Archeologia subacquea. Studi, ricerche e documenti I. Roma, pp. 21–48.

Di Fraia, G. (2019) ‘Baia: un quarantennio di studi e ricerche’, in Erto, M. (ed.) Bacoli 1919-2019. Cento anni di storia. Nocera Superiore: D’Amico Editore, pp. 37–94.

Maniscalco, F. (2004) ‘Il Parco Sommerso di Baia’, in Maniscalco, F. (ed.) Tutela, conservazione e valorizzazione del Patrimonio Culturale Subacqueo. Napoli: Massa Editore, pp. 195–202.

Maniscalco, F. and Severino, N. (2002) ‘Recenti ipotesi sulla conformazione del lacus Baianus’, Ostraka, 1.

Miniero, P. (2003) Baia. Il Castello, il museo, l’area archeologica. Napoli.

Miniero, P. (2010) ‘Baia sommersa e Portus Iulius: il rilievo con strumentazione integrata Multibeam’, in Blackman, D. J. and Lentini, M. C. (eds) Ricoveri per navi militari nei porti del Mediterraneo antico e medievale. Atti del workshop – Ravello, 4-5 novembre 2005. Bari: Edipuglia, pp. 101–108.

Petriaggi, R. (2005) ‘Nuove esperienze di restauro conservativo nel Parco sommerso di Baia’, Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea, 2, pp. 135–148.

Petriaggi, R. and Davidde, B. (2007) ‘Restaurare sott’acqua: cinque anni di sperimentazione del NIAS-ICR’, Bollettini dell’Istituto Centrale per il Restauro, (14), pp. 121–141.

Scognamiglio, E. (1993) ‘Il rilievo di Baia sommersa. Note tecniche e osservazioni’, Archeologia subacquea. Studi, ricerche e documenti I, pp. 65–70.

Scognamiglio, E. (1997) ‘Aggiornamenti per la topografia di Baia sommersa’, in Archeologia subacquea. Studi, ricerche e documenti II. Roma: Istituto poligrafico e zecca dello Stato Libreria dello Stato, pp. 35–46.

Scognamiglio, E. (2002) ‘Nuovi dati su Baia sommersa’, in Archeologia subacquea. Studi, ricerche e documenti III. Roma: Istituto poligrafico e zecca dello Stato Libreria dello Stato, pp. 47–56.

Scognamiglio, E. (2006) ‘Baia sommersa. Alcune considerazioni sulla carta del Lamboglia (1959 – 1960)’, Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea, 3, pp. 57–63.

Stefanile, M. (2012) ‘Baia, Portus Julius and surroundings. Diving in the Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Bay of Naples (Italy)’, in Oniz, H. and Cicek, B. (eds) Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Underwater Research – Antalya-Kemer 2012, pp. 28–47.

Stefanile, M. (2016) ‘Underwater cultural heritage, tourism and diving centers: the case of Pozzuoli and Baiae (Italy)’, in IKUWA V – Actas del V Congreso Internacional de Arqueología Subacuática Un patrimonio para la humanidad. Cartagena, 15-18 de octubre de 2014, pp. 213–224.

Insights

Marine bioerosion of limestone tesserae is a process that leads to the destruction of the substrate deriving from biological mechanisms such as perforation, abrasion, and corrosion caused by boring microorganisms (algae, fungi, bacteria), and macroorganisms (bivalve molluscs, sipunculans, polychaetes, and sponges). Bioerosion can be limited to the outer surface of the material and is generated mainly by the activity of the “grazers”, herbivorous organisms like echinoderms, gastropod molluscs, and some fishes that “graze” on the substrate, thus detaching considerable portions of the mosaic. Bioerosion may also reach the inner substrate and produce internal cavities whose dimensions and forms may vary, depending on the kind of boring endolithic organisms.

The white mosaic tesserae made of limestone in the Villa of the Pisones suffered from biological colonisationmm, both epilithic (superficial) and endolithic (bioerosion), which mainly affected the inner parts of the material.

Underwater image of the north side of the mosaic in white tesserae at Villa of the Pisones

The parts without sediment were populated by widespread thallii of encrusting red algae, whose covering action played a bioprotective role against marine erosion and settlement by other organisms. In fact, these calcareous layers bio-constructed by algae are a few millimetres thick; this can reduce the degradation on the surfaces of the tesserae. Other fouling organisms are present, such as Thoracica (barnacles), serpulids (marine worms) and Bryozoans.

In different seasons, the mosaic becomes alternately covered by a thin biofilm and by algal macroscopic blooms belonging to various systematic groups (Clorophyceae, Phaeophyceae, Rhodophyceae).

The exposed surface of the tesserae was affected by the growth of endolithic microorganisms, photosynthesizing autotrophs (distinguishable by the green colour of the colonised layer, such as cyanobacteria and microalgae – see the photo below), and heterotrophs (fungi) that settled in the stone by digging tunnels and galleries, whose forms and dimensions are recognisable thanks to the treatment with polyester resins. This allows for obtaining moulds that perfectly match the body of the endolithic microorganism responsible for the degradation (see the following image).

A peculiar growth of endolithic microalgae is the one caused by the development of Acetabularia acetabulum, a unicellular alga with an apparatus of anchorage capable of chemically perforate a limestone substrate. This apparatus is similar to the roots of a plant and is articulated in short and stocky ramifications with rounded apexes (see the image below).

The most prominent animal biodeteriogens of mosaics are boring sponges, belonging to macroborers. Their presence is clearly recognisable by minute subcircular holes (pitting), visible on the exposed surface of tesserae and hosting the osculi (filtering structures of a sponge). Inside the tesserae it is possible to find bio-eroded cavities, often confluent, which may host the entire body of an animal. The image below shows the main characteristics of the degradation, the morphological elements useful to recognise such animals and the mechanism of bioerosion.

Another peculiar type of degradation is the one produced by a bivalve mollusc, Rocellaria dubia. Some parts of the mosaic at Villa of the Pisones show a thick colonisation recognisable by 8-shaped holes that, although small-sized, are linked between each other inside the stone through very large cavities in which the molluscs are able to settle (see the photo below). The concomitant presence of multiple specimens inside a tessera may compromise in an inevitable way the integrity of the artefact. The 8-shaped holes are used by the animal to make its siphons protrude and filter the water. The holes are generally surrounded by a thin layer of aragonite secreted by the mollusc that can pile up even to a few millimetres, allowing the animal to carry out its vital functions even in presence of sediment layers.

Other boring macroorganisms are sipunculids and polychaetas, whose characteristics and ways of degradation are shown in the images below.

The Nymphaeum of Punta Epitaffio

The Submerged Imperial Nymphaeum of Punta Epitaffio is a site of extraordinary importance for the history of underwater archaeology and a true symbol of the underwater Baiae. In this submerged environment below the calc-tufa stone promontory of Punta Epitaffio, research and documentation campagns have been carried out since the end of the 50s, when the father of Italian underwater archaeology, Nino Lamboglia, found an ideal space to experiment the survey of an ancient building in an underwater environment by means of square grids.

The plans produced in those pioneering campaigns were then updated during the extensive works of excavation and documentation carried out in 1982 and guided by Piero Alfredo Gianfrotta and Fausto Zevi. After a sea storm in 1969, the building – already considered a prominent part of the ancient imperial palace of Baiae – returned two statues deeply corroded by marine organisms.

The campaigns of 1982 allowed for bringing to the surface all the other surviving statues and for assigning their iconographic interpretation to Bernard Andreae. So it was possible to understand that the environment was a nymphaeum-triclinium, i.e. a grandiose hall for banquets that was connected to the water. It had an extraordinary sculptural decoration inspired by the Odyssey, just like the famous Grotto of Tiberius in Sperlonga. In fact, the apse, built as a fake cave according to the customs of the time, depicts the scene that preceded the blinding of the cyclops Polyphemus, with Ulysses in the act of passing a jug of wine, helped by a friend, to the monstrous shepherd. This scene perfectly suited a space dedicated to banquets and wine; this antique and very common iconography made the space look as a sumptuous fountain.

The other statues, among which two effigies of Dionysus, one of which with a panther, are also recalling wine and the appearance of the members of the emperor’s family, in particular of the closest family members of the emperor Claudius to whom the reorganisation of the supposedly Augustan Nymphaeum was attributed: Antonia Minor, Augustus’ niece and Claudius’ mother, in the scheme of a Kore Albani, and the little Octavia Claudia who died very young.

Moreover, the operations carried out in 1982 had the merit of experimenting and improving the principles of stratigraphic archaeology in underwater environments and of understand the dynamics that took place in a period covering more than six centuries. The sunken building was documented as if it was a site on the mainland by taking every element into consideration, from the risible traces of the early construction stages until the coin from the Justinian age.

Recently, the Nymphaeum of Baiae has been converted in a large laboratory-museum for the enhancement of underwater cultural heritage. First the statues were kept in a space opened in 1997 at Torre Tenaglia at the Aragonese Castle of Baia, where the National Archeological Museum of Campi Flegrei is located, along with a reconstruction in a slightly reduced scale of the entire building.

Then, in 2009, modern replicas of the statues were in the underwater site, maybe the most visited one in the Underwater Archaeological Park of Baia, thus creating an exceptional underwater itinerary for tourists coming from every corner of the world.

In the meantime, the research went on and returned a clearer picture of the bonds between the Nymphaeum and the nearby buildings (among which a remarkable thermal complex) and of the function of a long stretch of paved road, splendidly preserved and easily recognisable on the seabed.

Andreae, B. (1983) L’immagine di Ulisse. Torino: Einaudi.

Avilia, F. and Caputo, P. (2015) Il ninfeo sommerso di Claudio a Baia. Napoli: Valtrend Editore.

Borriello, M. and D’Ambrosio, A. (1979) Baiae-Misenum (Forma Italiae. Regio I, XIV). Firenze.

Caputo, P, Severino, N. (2008) ‘Parco Sommerso di Baia: il restauro paesaggistico-ambientale di Punta Epitaffio, il recupero della strada Erculanea e i servizi per la fruizione delle aree archeologiche sommerse’, in Escalona, F. and Ruggiero, R. (eds) Il Progetto Integrato Campi Flegrei. Napoli, p. 56.

Lombardo, N. (2009) ‘Baia: le terme sommerse a Punta dell’Epitaffio. Ipotesi di ricostruzione volumetrica e creazione di un modello digitale’, Archeologia e Calcolatori, 20, pp. 373–396.

Miniero, P. (2003) Baia. Il Castello, il museo, l’area archeologica. Napoli.

Zevi, F. (1983) Baia. Il ninfeo imperiale sommerso di Punta Epitaffio. Banca Sannitica.

Zevi, F. and Miniero, P. (2008) Museo Archeologico dei Campi Flegrei, Catalogo generale, 3, Baia, Liternum, Miseno. Napoli

ISCR projects in Baiae

In 2003, the Underwater Archeology Operations Unit (NIAS) of ISCR, created in 1997, undertook scientific activities in the Underwater Archaeological Park of Baiae under the direction of Roberto Petriaggi.

The NIAS, with the project Restaurare sott’acqua (Restore Underwater), started in 2001 in line with the principles of UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, was the first one in the world to study and experiment instruments, materials, methodologies and techniques for the restoration and conservation in situ of submerged ancient artefacts. These experimental restorations were carried out in Villa of the Pisones, in the villa with a prothyrum entrance, in a sector of the Via Herculanea, in the thermae of Punta dell’Epitaffio and in a building with a porticoed courtyard in the nearby Portus Iulius. Moreover, the Data Cards known as SAMAS and SAMAS Bio were developed and tested during the surveys. Inspired by the criteria of the Charter on the Risk for Cultural Heritage, the cards allow for conducting an effective census of submerged structures and critical issues found during the operations in water and, at the same time, for offering a valid tool to define the conservation works to be planned by the designated authorities.

The activities of NIAS in Baia have continued in recent years under the guidance of its new director, Barbara Davidde Petriaggi, thanks to European funds and large collaboration networks with national and international partners.

During the MUSAS project, the sites of Villa of the Pisones and Nymphaeum of Punta dell’Epitaffio have been the subjects of new studies and evocative 3D reconstructions which will form the basis for a new enhancement initiative.

The users will be able to enjoy the underwater heritage not only on the Web through the Portal-Museum of Underwater Archaeology, but also while diving, thanks to tablets and advanced devices for augmented reality that will allow for communicating through an experimental network (the “Internet-of-Underwater-Things”) and, at the same time, for continuously monitoring the site.

In BlueMed project, ISCR was able to restore an evocative mosaic of wrestlers, recently discovered in the area of the Villa with prothyrum entrance, and to include Baiae among the pilot sites in Europe for the creation of new online itineraries and to preserve the submerged archaeological heritage.

Yet another European project, iMareCulture, allowed for further advancing the study of the Villa with prothyrum entrance, leading to a 3D reconstruction for virtual and augmented reality applications.

Last but not least, the project named Sibilla, by means of a specially developed platform, will allow for the realisation of an integrated cloud-based system to preserve and enhance the cultural heritage by creating a network of the underwater and mainland sites of Baiae and the Archaeological Park of Paestum.

During seventeen years of activity in the submerged area of Baiae, ISCR managed to recover and create underwater routes to explore some iconic sites, contributing to the conservation of fragile and endangered materials and to a deeper knowledge of the rich cultural heritage disseminated in the area that once surrounded the Lacus Baianus. Today, many of these activities are best practices, recognised on an international level and constitute a reference for the conservation of submerged architectural sites in many places in the world.